The Challenge of Early Recognition

Primary myelofibrosis (PMF), a Philadelphia-negative myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN), can present as a de novo condition or secondary to polycythemia vera (PV) or essential thrombocythemia (ET). The 2016 WHO revision introduced a subclassification of PMF into “prefibrotic” and “overt fibrotic” stages, a distinction retained in the 2022 WHO and International Consensus classifications (see Table 1).1–3 Currently, the diagnosis of PMF relies on the 2022 WHO and ICC criteria, integrating clinical, laboratory, cytogenetic, and molecular findings.1,2,4 While key mutations of JAK2, MPL, and CALR are often present, they are not always definitive. PMF is characterized by bone marrow fibrosis, aberrant cytokine production, anemia, hepatomegaly, extramedullary hematopoiesis, and constitutional symptoms, with a potential risk of leukemic progression and subsequent shortened survival.5 Improvements in outcomes of PMF patients over the last decade have been attributed to key factors such as a deeper understanding of pathogenesis, earlier diagnosis, better risk stratification, increased use of JAK inhibitors, and enhanced supportive care.6 Unfortunately, the only currently available curative treatment is an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (alloHCT).7

Given the limited availability of curative treatments, optimizing therapeutic strategies and minimizing diagnostic delays are critical for improving outcomes in MPN. Patients with MPN often experience thrombotic complications either prior to or at diagnosis, which can significantly diminish their quality of life and increase the risk of recurrent thrombotic events.8 Diagnostic delays of up to 256 days have been reported, with 15% of patients experiencing potentially preventable thrombotic events during this period.8 Additionally, diagnostic discordance is a known contributor to delayed diagnosis and treatment initiation. In a study of 560 PMF patients at a referral center, discordance was found in 12.5% of cases, primarily due to lower grades of bone marrow fibrosis (0-1), lack of JAK2V617F mutation, and absence of peripheral blood blasts, emphasizing the need for a comprehensive evaluation. Referral to a tertiary center should be considered, especially for more complex cases.9 To minimize diagnostic delays, several practices are essential for a correct and timely diagnosis:

- Adherence to updated WHO and ICC criteria

- A multidisciplinary approach involving close collaboration between clinicians and pathologists

- Integration of clinical, laboratory, genetic and pathological features.10

The current NCCN guidelines recommend the use of risk models to inform treatment selection.11 To support this, the accompanying toolkit includes easily accessible links to risk model calculators for diagnosing PMF. While this article, designed to complement both the video and toolkit, offers additional guidance for clinicians in diagnosing PMF, the video provides a step-by-step overview of the diagnostic process. Together, the article, video, and toolkit deliver clinicians valuable insights and practical tools to optimize the timely diagnosis of PMF.

Workup of Suspected PMF

The initial evaluation of a patient with suspected myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) should include a thorough history and physical examination, palpation of the spleen, assessment of cardiovascular risk factors, a review of the patient's medication and transfusion history, and an evaluation of any bleeding or thrombotic events.4 Distinguishing primary myelofibrosis (PMF) from other myeloid neoplasms, such as myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML), is essential for accurate diagnosis and treatment.5 For instance, chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) must be excluded by evaluating for BCR-ABL1 transcripts using multiplex reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) or fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) on peripheral blood, particularly in patients with thrombocytosis accompanied by basophilia or left-shifted leukocytosis.4

Laboratory Evaluation

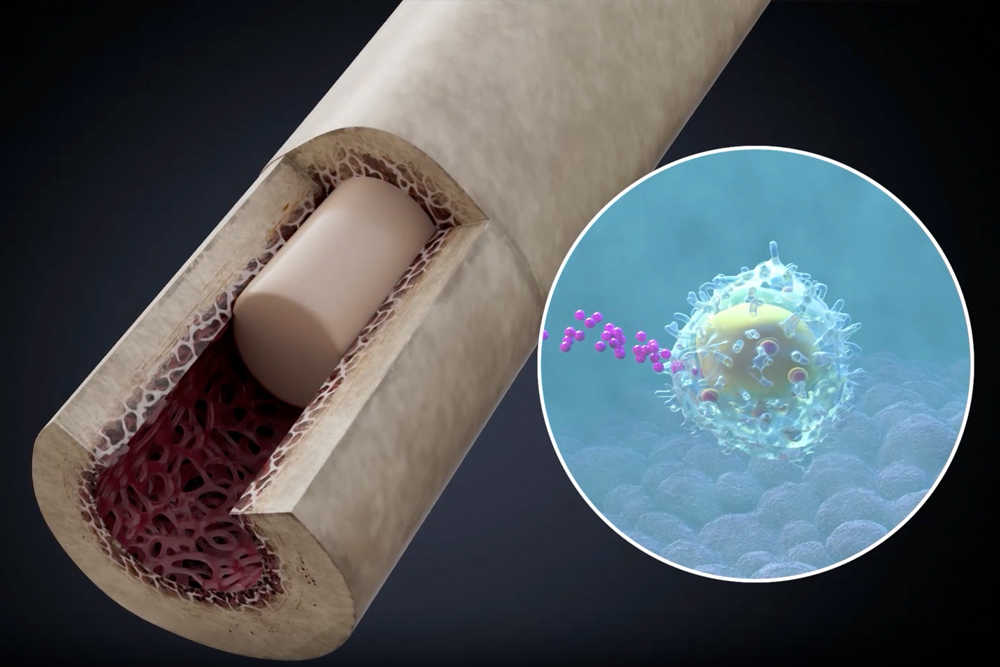

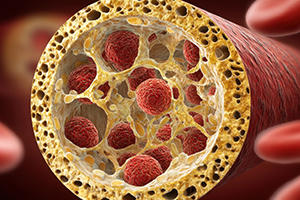

The following laboratory evaluations are recommended for patients with suspected primary myelofibrosis (PMF): complete blood count (CBC) with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), uric acid, serum lactate dehydrogenase, liver function tests (LFTs), serum erythropoietin (EPO) level, iron studies, and peripheral smear. If the patient may be a candidate for hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HCT), HLA typing should also be performed.4 While peripheral blood leukoerythroblastosis is commonly observed, it is not a required feature for the diagnosis of PMF.5 The diagnosis of PMF primarily relies on histopathological and molecular criteria.3 The bone marrow (BM) can be either hypercellular or hypocellular, with numerous megakaryocytes arranged in tight clusters showing pleomorphism and dysplastic features.3

BM aspirate is critical to accurately distinguish between disease subtypes, with varying degrees of fibrosis typically reported (grade 0-1 in pre-fibrotic MF and grade 2-3 in overt fibrotic MF).3 BM fibrosis is often associated with key driver mutations12 (present in approximately 90% of cases) as well as additional genetic alterations (e.g., ASXL1, SRSF2, EZH2, IDH1/2, U2AF1), which play a critical role in disease pathogenesis and prognosis.3,5 Mutations such as ASXL1, SRSF2, and U2AF1-Q157 are associated with poorer survival, while Type 1/like CALR mutations correlate with better survival. Additionally, mutations in RAS/CBL predict resistance to ruxolitinib therapy, underscoring the importance of assessing these mutations before initiating treatment.5 Molecular testing should be conducted using a multigene next-generation sequencing (NGS) panel on blood or BM, which not only identifies key mutations but also detects secondary, tertiary, and quaternary mutations that may have prognostic significance.4 Lastly, BM examination with cytogenetic and mutational analysis should also be integrated with patient symptoms.5

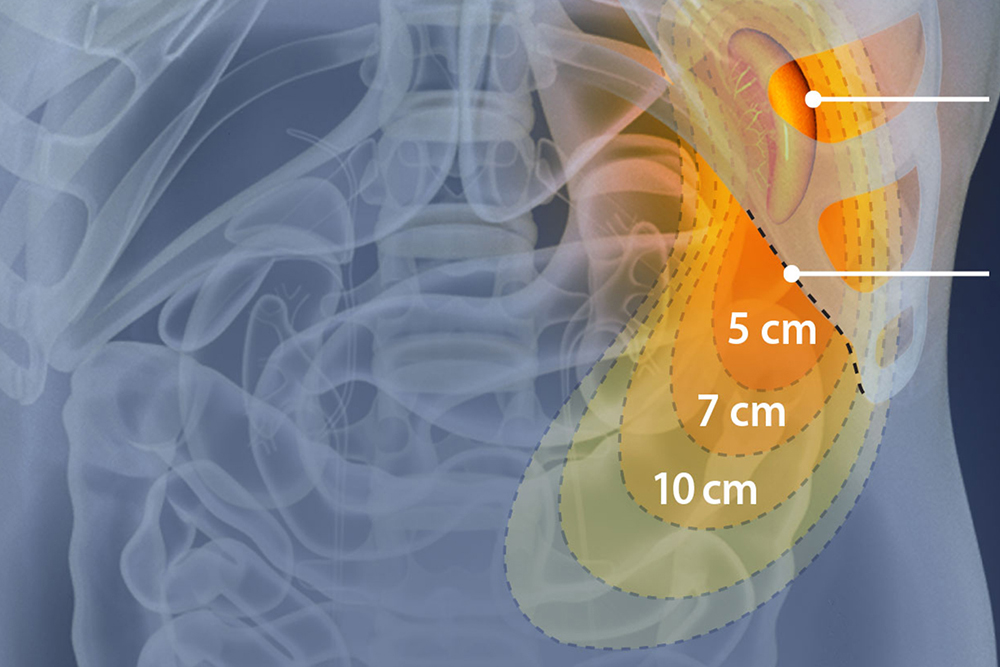

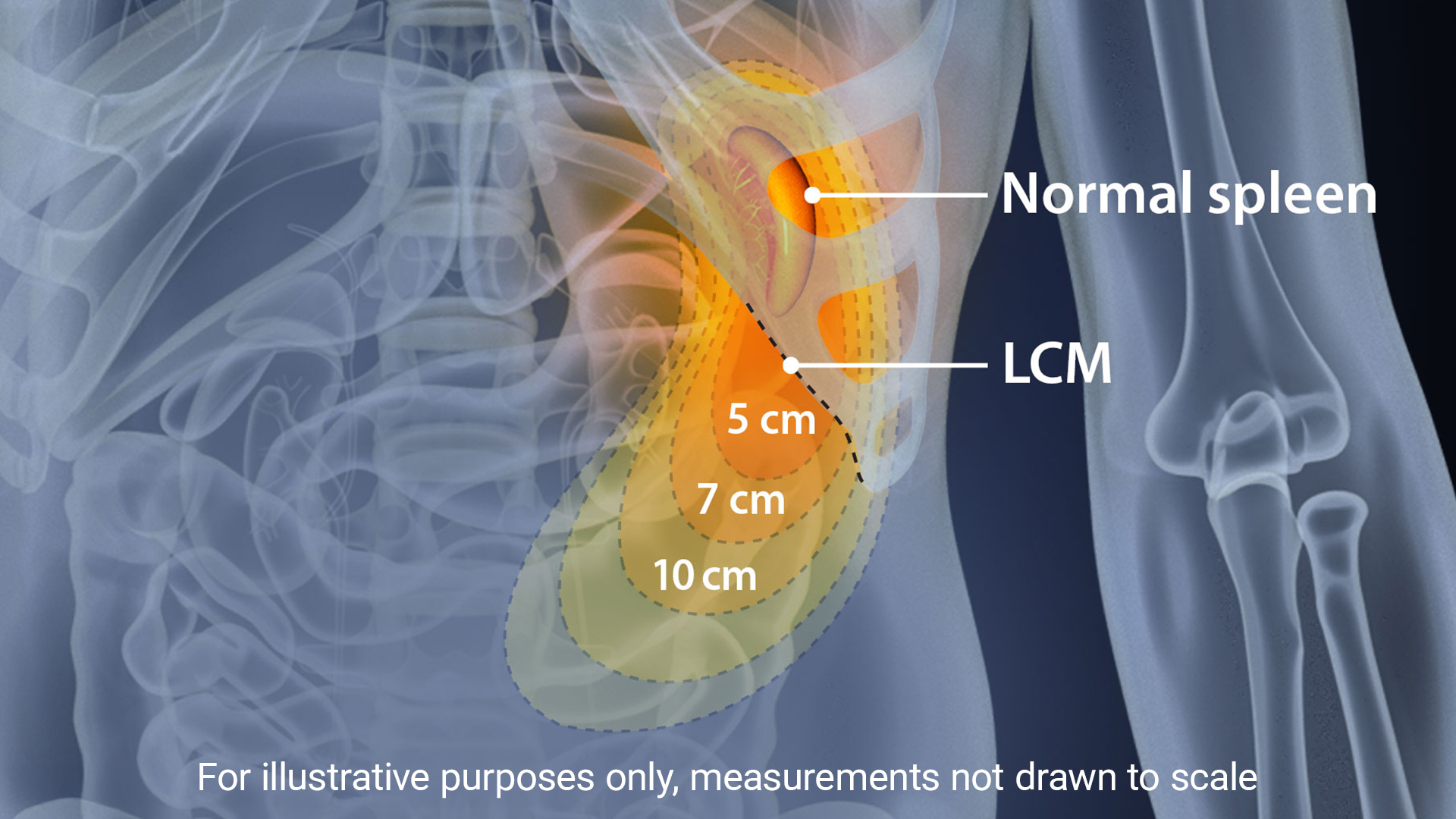

Assessment of Splenomegaly

Splenomegaly, a common feature of MPNs, is considered a minor diagnostic criterion for PMF, present in both the prefibrotic and fibrotic stages of the disease.11 The incidence of palpable splenomegaly is higher in patients with early and prefibrotic PMF compared to those with essential thrombocythemia (ET).11 Reducing spleen size and managing related symptoms have long been therapeutic goals in PMF, and splenomegaly management remains a key marker and inclusion criterion in many clinical trials. The revisions to the 2013 IWG-MRT and ELN response criteria introduced three new categories to assess improvements in splenomegaly.11 Early intervention and a positive response to spleen reduction have been linked to improved survival. In the COMFORT-I and COMFORT-II trials, patients treated with JAK inhibitors demonstrated significant improvements in spleen volume and symptom burden, with greater reductions in spleen length correlating with longer overall survival (OS).13 Additionally, patients who experienced spleen reduction with JAK inhibitors prior to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HCT) had lower relapse rates and better 2-year event-free survival.14

Intricacies in Diagnostic Evaluation

The diagnosis of PMF is often complex because it shares many features with other myeloid disorders. Until recently, available prognostic scoring systems in primary myelofibrosis (PMF) did not integrate clinical, histological, and molecular data.15 Now, several contemporary prognostic systems do, including the genetically inspired prognostic scoring system (GIPPS) and mutation- and karyotype-enhanced international prognostic scoring system (MIPSS70+ v2), underscoring the importance of knowing the difference between them and their utility5 (see Table 2). Prognostic scoring systems continue to evolve and incorporate clinical, genetic and molecular aspects of the disease to risk stratify patients into unique subgroups based on projected overall survival. This aids in proper patient counseling about expectations and goals of care, appropriate triage for the need and timing for stem cell transplantation, guides JAK inhibitor therapy, and helps stratify patients for clinical trial enrollment. This module’s toolkit contains brief descriptions of each scoring system, suggests the patient population it may be most useful for, and provides an external link to the calculator.

Diagnostic Dilemmas

Triple-Negative PMF

Familiarity with the mutational profile of MPN not only supports the diagnosis but could also offer valuable prognostic insights. Notably, approximately 10-15% of patients with PMF do not express any of the 3 key driver mutations and are therefore referred to as “triple-negative;” however, mutations might be present.16 NGS testing is quite beneficial in this patient population as it can identify the presence of somatic mutations and cytogenetic abnormalities due to the wide array of its panel. Some of the clonal abnormalities identified through NGS can help hone in on the diagnosis of PMF, especially when incorporated into the morphologic and clinical context. Given that triple-negative status is associated with inferior overall survival and leukemia-free survival, timely, accurate diagnosis is critical.11,16

Younger Patients

Currently, approximately 10-20% of MPN patients are less than 40 years old, and very few cases of this patient population have PMF; hence, data for management is limited. Often clinical risk score calculators fail in younger patients.7 A different approach is required for the disease management of a younger patient. With longer life expectancies, patients also face different psychosocial needs, fertility and pregnancy planning needs to be incorporated as part of therapy, and challenges such as long-term side effect management, especially the occurrence of secondary cancers must be considered.7

Final Thoughts

Diagnosing primary myelofibrosis (PMF) accurately and without delays is critical due to its shorter OS and increased risk of acute leukemic transformation compared to other MPNs. The diagnosis of both overt and pre-fibrotic PMF requires a comprehensive approach, incorporating clinical, morphologic, and molecular/genetic findings and necessitating close clinician and pathologist communication.

References